Critical Thinking: an inside look at our Lincoln Park case study

In April of 1876 Frederick Douglass stood at the intersection of East Capitol and 11th Streets in Washington, DC to speak at the unveiling of a statue. In the crowd of 25,000 people were President Ulysses S. Grant, Mary Todd Lincoln, Members of the Cabinet and Congress, and many formerly enslaved people.

I imagine Douglass standing serenely, with the statue behind him, the crowd in front of him, and, directly down East Capitol Street, just visible through what would have been early spring buds, the U.S. Capitol.

He begins by describing the statue as “a highly interesting object” (perhaps a clue to his opinion of it) and goes on, in typical Douglass fashion, to honor the occasion and speak his truth.

143 years later a smaller group of people gathers in what is now called Lincoln Park to look at the same statue, which stands in the same place, though now facing away from the Capitol. There aren’t any sitting presidents or acting Members of Congress in this crowd of 24, though I’d be very surprised if there weren’t several future government leaders present. Lincoln Park is lined with trees and benches, the young couples with kids strolling through outnumbered only by the young couples with dogs. There is a small playground on one end, people jogging around the circumference, and occasional outdoor yoga when the weather is nice. It is hard to imagine that this same location was once a hardscrabble Union Army medical camp. The soldiers jokingly called it Mr. Lincoln’s Hospital, and after the Civil War it became the first of many public places officially named after the former President.

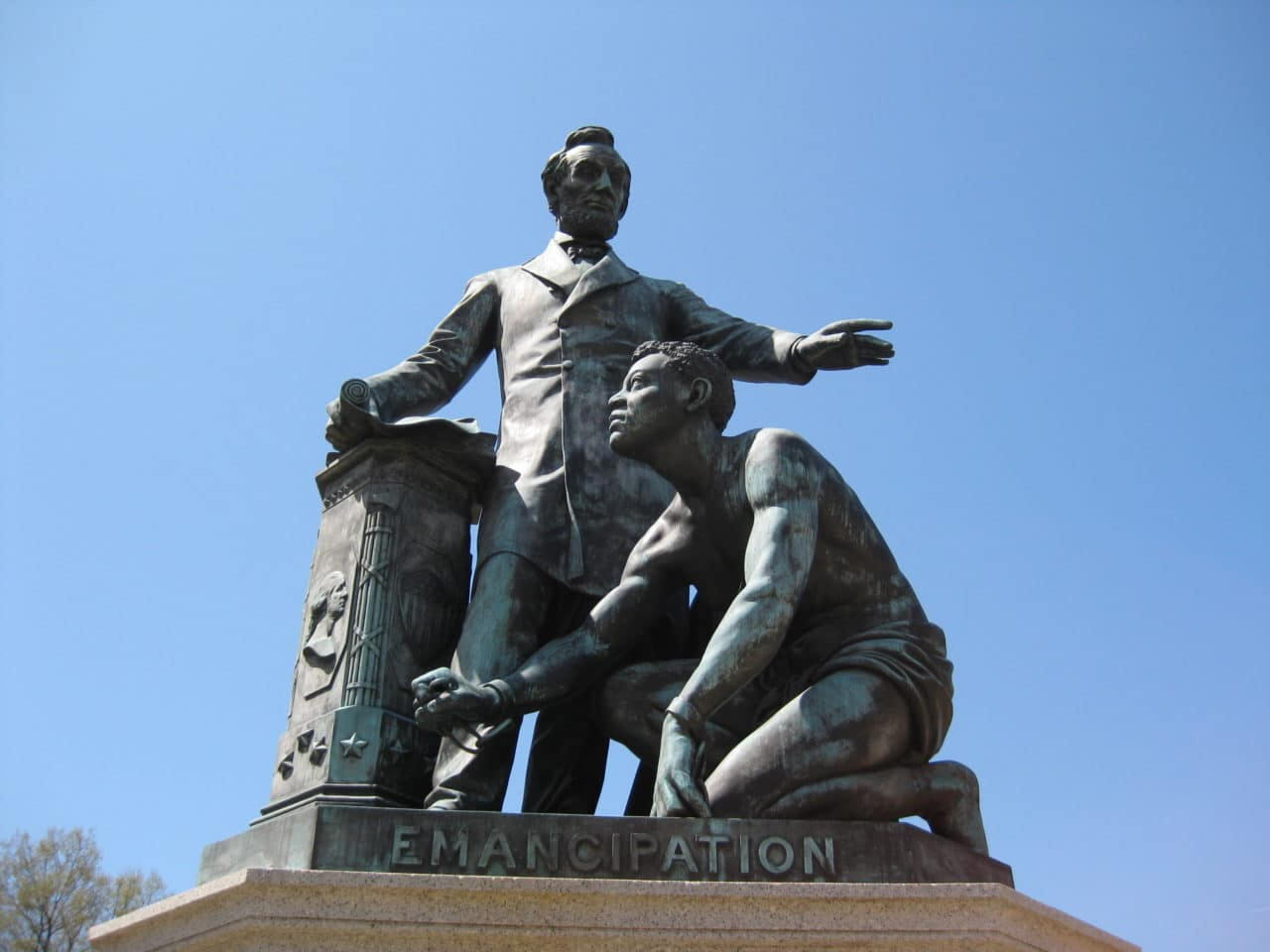

These future leaders eye the statue warily. They see a barely-clothed African American kneeling at Lincoln’s feet. It seems old-fashioned at best. Offensive and worthy of removal at worst.

Douglass was charged with giving a commemorative speech on the day the “highly interesting” statue was unveiled. Our students have a different charge, one that puts their growing critical thinking skills to the test: *What is the best future of this statue? Should it still stand in a public place? If not, where is the appropriate place for it? Should it be destroyed, or altered? Should an explanatory plaque be added, and if so, what should it say?

The students begin without any information about the history of the park or the statue. All they know is their charge, and all they have to help them is SEGL’s STAR (SEE, THINK, ACT, REFLECT) critical thinking model.

That model is informed by intensive faculty discussions about the best way to teach critical thinking in 2019, an era where respect for institutions is at low ebb and reliance on social media is at an all-time high. How do we teach students the value of reason when our public conversations prize emotional release? How do we do these things without violating one of the SEGL faculty’s cardinal rules: to remain nonpartisan? Armed with assistance from the Foundation for Critical Thinking (we found Richard Paul’s work on Dialogical Thinking particularly valuable), Harvard University’s Project Zero (whose “See-Think-Wonder” routine helped inspire our model), and others, we created the STAR model.

The SEE step for this challenge seems straightforward: students make a list of all the things they notice about the statue, without jumping to judgments. (We use a Project Zero thinking routine called “Looking Ten Times Two” that encourages students to go beyond first glances.) Don’t say that Lincoln is blessing a slave: instead, note that he is holding his left hand in front of him at waist level about a foot above an African American man on one knee. Don’t say that the enslaved person is unhappy; instead, note that he has fixed his stare into the distance above him. In a world that incentivizes forming quick, rather than informed, opinions about so many things, this first step of our critical thinking routine is harder than it seems.

Only after students take an inventory of everything they notice about the object in front of them do we start step two: THINK. In partners, after sharing lists, they begin to judge, conclude, guess, and evaluate. This is the step where they put pieces together. They ask each other questions and push their partners to explain why they think what they do.

After letting students make some judgments on their own, we gave them more background information to consider, alongside their initial lists of observations:.

The statue, called the Freedman’s Memorial (or sometimes the Emancipation Memorial) was erected 1876 in what was then called Lincoln Square (now Lincoln Park). Charlotte Scott, a recently freed African American woman, came up with the idea to raise a statue honoring Lincoln shortly after his assassination, and donated the first $5 for the project (it was supposedly the first $5 she earned as a free woman). Scott’s donation was just the beginning – the money that funded the statue was donated almost entirely by formerly enslaved people. The monument was sculpted by Thomas Ball, a white man. The statue’s donors made changes to Ball’s original design: for example, they asked for him to remove the “liberty cap” that originally was to cover the emancipated man’s natural hair, and they asked that he be modeled after a real person. (Archer Alexander, one of the last men to be captured under the controversial Fugitive Slave Act, was ultimately chosen.)

Did the students’ initial conclusions change after going deeper into their observations and the statue’s history? Absolutely. For example, several who were ready to tear down the statue as soon as they saw it discovered they weren’t as certain that was best. Some stuck with their original position but were better able to articulate the other side’s point of view. Others simply gained a better understanding of how complex the decision making process is.

Armed with their observations, their initial thoughts, and now some more background information, we asked our group of students to ACT. Leaders rarely have the luxury of postponing decision making. At some point, even with imperfect information, they have to act! Imagine you are the head of the National Parks Service (which runs Lincoln Park), we asked, or a sitting member of Congress (which allocates the funds for national parks), or the Mayor of DC (who responds to concerns from DC residents). What do you do about this statue? Unsurprisingly, there wasn’t a consensus on what the right decision was, but each student’s choice was grounded in thorough understanding and collegial idea-sharing.

On the chilly 10-block walk back to the dorms, students did the final step in our critical thinking routine: REFLECT. Why did I make the decision I made? What were the main factors that led me to my decision? Why did some of my peers make a different decision? What factors might have swayed me in another direction? How will my decision impact the people around me? What might I do differently next time? What do I want to know more about?

Douglass spends much of his speech assessing Lincoln, often in unflattering terms that would surely have been hard for some to hear: “It must be admitted, truth compels me to admit, even here in the presence of the monument we have erected to his memory, Abraham Lincoln was not, in the fullest sense of the word, either our man or our model.”

Towards the end, however, Douglass says this:

Despite the mist and haze that surrounded him; despite the tumult, the hurry, and confusion of the hour, we were able to take a comprehensive view of Abraham Lincoln, and to make reasonable allowance for the circumstances of his position.We saw him, measured him, and estimated him; not by stray utterances to injudicious and tedious delegations, who often tried his patience; not by isolated facts torn from their connection; not by any partial and imperfect glimpses, caught at inopportune moments; but by a broad survey, in the light of the stern logic of great events . . .*

In the mist and haze that surrounds our “fake news” era, despite the tumult, hurry, and confusion of our current political climate, our students were able, I think, to take a comprehensive view of the Emancipation Memorial. They made reasonable allowances for the circumstances in which it was designed and built. They saw it, measured it, and estimated it, not by considering isolated facts torn from their connection, nor by partial and imperfect glimpses, but by a broad survey in the light of stern logic.

I think Douglass would have approved.