Journalism, Story-telling, and Truth: Week 4 in South Africa

What is true, and how do you know? Now that you know, what will you do about it? These questions are at the core of the media literacy case study that SEGL at ALA students participated in last week.

Following their conversation with Simon Allison of the Mail & Guardian, students dove straight into an exercise designed to help them understand the challenge of modern news production and consumption. After asking students to write down the news sources they used most, we asked all students to arrange those sources on a matrix. On the “x axis” of that matrix was the liberal-conservative spectrum; on the y-axis, how reliable each source was. The results were fascinating and showed both assumptions and blind spots in our group’s favorite news sources; it also helped create many questions for our next guest expert.

The next day, our students met with Ryan Lenora Brown, an American journalist based in Johannesburg. A freelance reporter and an Africa correspondent for The Christian Science Monitor, she has reported from nearly two dozen countries on the continent, and in addition to The Monitor has been published in The Washington Post, The New York Times Magazine, Runners World, Newsweek, The Atlantic CityLab, ForeignPolicy.com, The Daily Beast, The Chronicle of Higher Education, Al Jazeera, U.S. News and World Report, and The Guardian, among others. Students had to ask her all kinds of questions, from the general (How can we change the way that Africa is portrayed by western media? Does journalism, as an industry, hold itself accountable for how it represents the African continent?) to the specific (After reporting on the role of the U.S. government in preventing African textile companies from flourishing, how has your view of the U.S. and international trade changed?) to the personal (How has being a woman affected your career in journalism?) It was a robust and enlightening conversation.

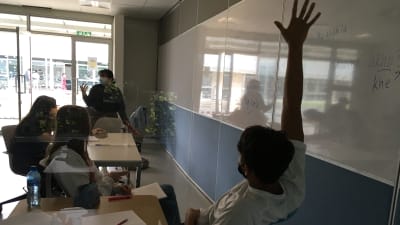

With a solid sense of how to report (and not to report) on Africa, the students took on a two-day journalistic simulation based around the Ugandan presidential election last month. In small groups, the students were assigned to both campaign press teams and various media outlets on deadline to their exacting publishers at the prestigious Hatori, Mphahlele, and Nguyen (HMN). Throughout these two days, our E&L team dropped new and often conflicting information to the students, who had to determine which information was accurate and what to ignore. On the first day, they worked collaboratively to produce a paragraph of reporting and a tweet from the “campaign trail”; on the second day, each group had to record a 2-minute video summarizing the campaign and the election results. As the guidelines told them, “You will not have perfect information, nor will you have all the clarity you might like. In an imitation of life, this simulation will ask that you be flexible and do all the best you can with what information you have.” Here are a few of their tweets:

From the BBC: After 36 years in office, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni has launched his new campaign. His opponent, pop star-turned-activist Bobi Wine, launched his “National Unity Platform” today.

From The Independent (a nonpartisan, politically neutral local Ugandan magazine): Uganda’s Electoral Commission has banned campaigning due to COVID-19. One day after President Museveni nominated himself for a 6th term, Bobi Wine launched his National Unity Platform Party, which he says is the new political wing of the People Power Movement.

From The Continent (known for its cheeky rhetoric): We’re covering the Ugandan election. Apparently the president is taking COVID-19 measures really seriously, against the opposition at least.

From Bobi Wine’s press team: Vote Bobi Wine as the next president of the Republic of Uganda. Bobi Wine is a strong promoter of social justice and overall improvement within the country, which can only happen with a change of administration. Bobi Wine cares for all Ugandans and guarantees a brighter future.

They had to be accurate, succinct, and true to the reputation of their assigned news source or campaign. We were impressed!

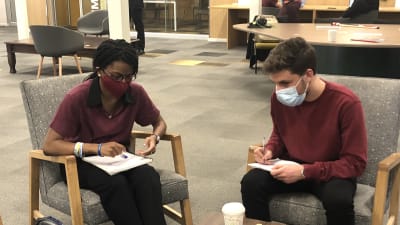

In English class last week, in addition to dissecting texts that represent western portrayals of Africa and African portrayals of the west, we created our own story exchange project, modeled after Narrative 4’s work on empathy development. Students were paired up randomly and picked a story from their lives to share with their partner. The partner took notes, asked follow-up questions, and produced a first-person narrative of the story to deliver to the class as if it were their own story. The topics ranged from deeply personal to hilariously funny, and it’s safe to say that both English classes–made up of SEGL students and ALA students–felt newly connected after this experience.

This week, the students participated in a longstanding ALA tradition called “Seminal Readings.” Check back next week for a summary of that experience and some student takes on it! This week, Audrey Liu, a current student from New York City, shares a reflection based on a journal entry she wrote for English class last week:

When I was in 9th and 10th grade, I participated in a few Model United Nations simulations. Recently, my Model UN experience has been bothering me, and here’s why: I’ve come to realize that our solutions, or “resolutions,” were usually a) unrealistic, and/or b) Western-centric. What I mean by the latter was the presence of the very Radi-Aid-esq dynamic of U.S. kids thinking that they could (and should) solve the world’s problems for them. This was rough given that most students completed as little research as they could and were above all else trying to “win” (ie: seem in control and speak as much as possible, even to the detriment of other, smaller nations). Not only did we never consider the ways in which U.S./Western powers’ international bullying and greed has led to many of the issues we tried to “solve,” but most American participants also followed the neocolonialist playbook—dangling aid or money in exchange for “democracy”—without considering the harms of this dialogue. Our lists of solutions were typically lengthy and poorly thought-out. Often, Model UN conferences had “good guys” (the U.S., England, etc.), “bad guys” (China, Iran, sometimes Russia, and various other ‘opposing’ Asian, African, and South American countries), and then “small countries” (the rest of the world not hegemonic or large enough to ‘matter’ either way). I recognize that I attended very few and small conferences, which may not be indicative of some larger, collegiate-run events, but even so, I wonder about Model UN as an institution in U.S. high schools (and globally—ALA has a Model UN team as well, though I imagine they bring quite a different outlook on it than most U.S. students). I recognize the value of the conversation around diplomacy, but I worry that the lack of thoughtfulness and discussion around colonial legacies might be outweighing any societal benefits that Model UN provides.

I contrast Model UN with my experience in my recent Health BUILD challenge. BUILD, “a fundamental pillar of Entrepreneurial Leadership [ALA’s signature course],” stands for Believe, Understand, Invent, Listen, and Deliver. It’s ALA’s framework for solving problems by encouraging students to gain a thorough understanding of a large problem and develop a specific “problem statement” before brainstorming the best ways to address it. BUILD also promotes listening, revising, and even failing because it recognizes that the first solution is usually not the best solution. I joined a two-week BUILD session focusing on access to healthcare with two peers, one from the DRC and one from Cameroon. I knew that I had limited knowledge about access to healthcare in those countries, let alone how to improve it, but it was fascinating to perform research with my teammates, who could also provide some personal perspective. Our collaborative approach was fun and refreshing, and I both learned from and enjoyed the experience.